Fitness

It’s one thing to know about anatomy in the abstract, but quite another to apply that knowledge to the training of someone else’s anatomy, given that each of our bodies is unique.

How much does a voice teacher really need to know about anatomy?

In the words of pedagogy expert and author Scott McCoy, “Enough to avoid saying anything that will make you sound like an idiot!”

How much does a fitness trainer really need to know about anatomy?

In the words of fitness trainer and author me, “Enough to avoid getting sued for injuring your client!”

How much does a middle school Physical Education [PE] teacher really need to know about anatomy?

There’s no funny-because-it’s-true response for this one. I think the answer may actually be “Nothing”.

That’s admittedly an incendiary way to frame the situation, so I will immediately explain where I am going with this.

Throughout this blog, I strive to distinguish between conceptual and practical learning; in a previous post, I discussed how my aptitude for “book learning” meant I generally did well on tests even if I had barely studied the material. For any skill set or area of inquiry, you can either dip your toe in or do the deep dive.

The extent to which our theoretical voice teacher, fitness trainer, and PE teacher really need to know about anatomy depends on what they intend to do with that knowledge:

- A superficial, conceptual acquaintance with anatomy will suffice for passing the tests required for their respective qualifying documents (diplomas, certifications, and so on).

- The ability to discuss anatomy without sounding like an idiot will suffice to get them through an interview and land a job.

- Deep conceptual and experiential knowledge of anatomy will facilitate outstanding performance in that job.

My point is that you can know enough anatomy to earn your degrees and certifications and then land a job, without necessarily knowing enough about anatomy to have that knowledge inform the way you perform the job. There’s a sense in which that part—the practical part, the part that determines whether you will become an effective teacher or trainer—is left to individual discretion.

My fitness certification is a perfect example. My certificate was conferred by The National Association of Sports Medicine [NASM] upon the successful completion of a big multiple choice test monitored in an over-air-conditioned, windowless room (just like the SAT!). The information for which I was being held accountable was supplied by an enormous textbook and supported by an online self-study course.

At no point did anyone observe me actually training a client.

The point of the certificate was not to attest to my excellence as a fitness trainer. The point of the certificate was to signal to potential employers and insurers that I am a low-risk proposition for them, i.e. I am less likely to injure a client and cost them a big settlement payout. While that enormous textbook does have lots of great information about anatomy and how to train it, I would estimate that close to a third of the material focuses on how to avoid getting sued for injuring a client.

How much does a fitness trainer really need to know about anatomy? Enough to avoid getting sued for injuring your client.

My experience of qualifying to teach voice at the college level was similar in this regard (with the notable exception that no one is requiring me to earn continuing education credits every two years the way that NASM does). In pursuit of my doctorate, I read all the vocal pedagogy books and passed a rigorous comprehensive exam. I don’t think that anyone on my doctoral committee, including the head of the voice department, had more than a passing acquaintance with vocal anatomy. At no point did anyone observe me actually teaching a student.

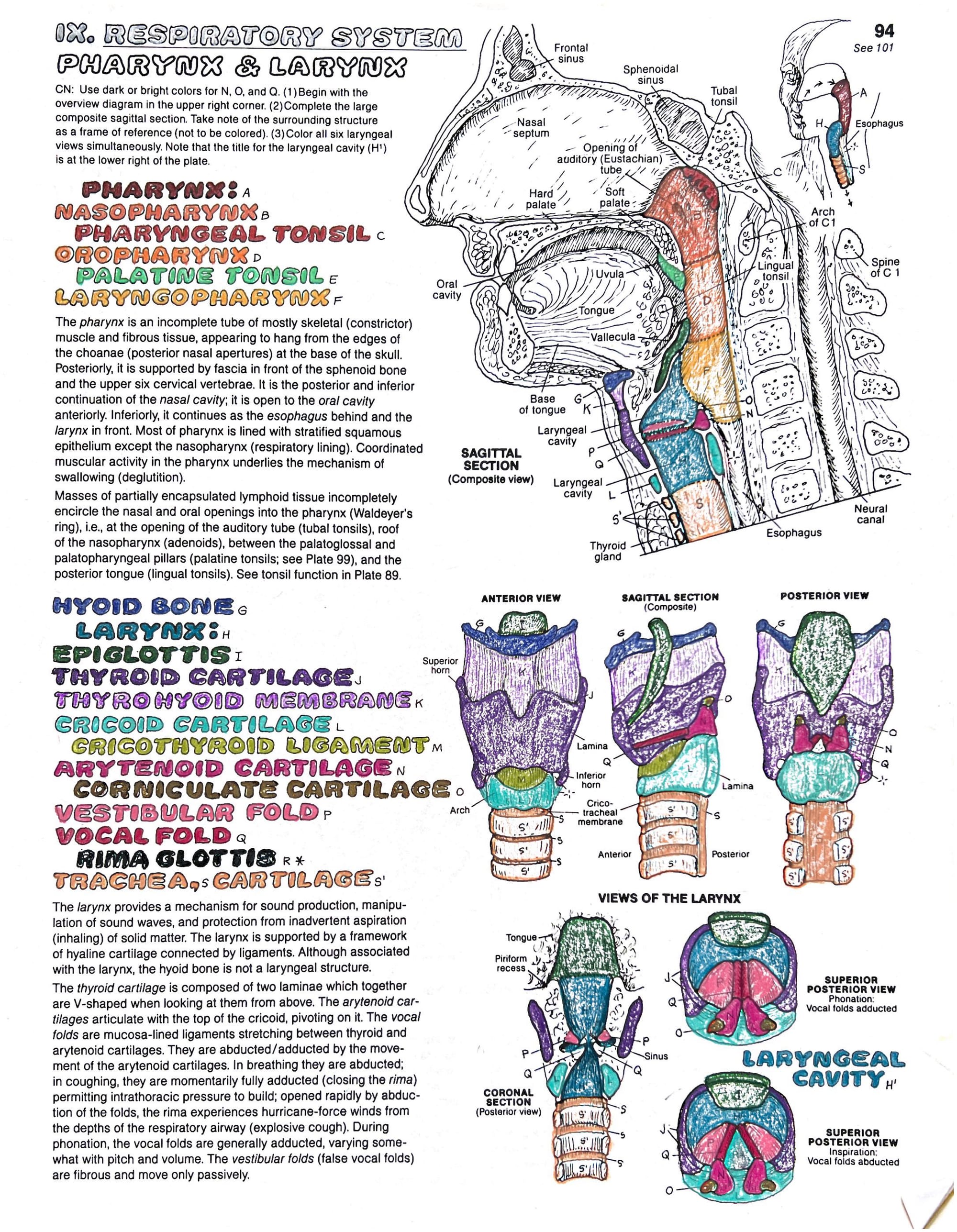

That is why, with my doctorate in hand, I despaired of becoming an excellent teacher—I knew that I needed a depth of anatomical understanding that I lacked, even if they didn’t. The anatomical illustrations in all of those vocal ped manuals had been appropriated from medical textbooks, and I had no idea how to interpret what I was looking at. I was able to memorize the terms and pass the tests, but I had almost no comprehension of how vocal anatomy worked at a practical level.

It took me almost twenty years to become what I consider adequately competent in this area.

Shortly after I completed my DMus in 1999, my artist brother-in-law gave me a copy of The Anatomy Coloring Book and a set of art pencils. That was such a great inroad for me! Fortunately (or unfortunately), an aptitude for biology was not something that the SAT cared about, and I was very intimidated by the idea of studying something for which I had demonstrated little aptitude. But I knew that this was information that I needed to master, and I would never have managed it without that coloring book.

The next step was achieving practical understanding. In 2002 I managed to get hired as a floor trainer at the (now closed) New York Sports Club at 62nd and Broadway. They were willing to risk taking me on while I worked on my fitness certification. I think they paid me $7 an hour to rack weights, wipe down treadmills, and offer advice to the members. From a career standpoint it would have been wiser for me to seek an assistant professorship at any school that would have me, but in retrospect I can validate that it really was more important for me to learn what I learned monitoring the basement floors of a mediocre NYSC.

That was how I gradually began to understand biomechanics. Observing and guiding the big, full-body movements my clients performed at the gym gradually enabled me to comprehend how the same biomechanics govern the comparatively small, subtle movements we perform inside our bodies when we sing.

My book on vocal anatomy and biomechanics came out in 2018, with a cover illustration contributed by the same guy who put the coloring book in my hands nearly 20 years earlier.

How much does this voice teacher really need to know about anatomy? Enough that it superseded my jockeying for an academic position and auditioning for opera roles! I knew that I would never be effective (or happy) in my work without a deep conceptual and experiential knowledge of anatomy.

From time to time, I hear that my book appears on the syllabus (and presumably the tests) for vocal ped courses at institutions where I have unsuccessfully applied for jobs, having squandered those post-doc years pursuing that knowledge rather than trying to sell what little I already had.

The irony is not lost on me.

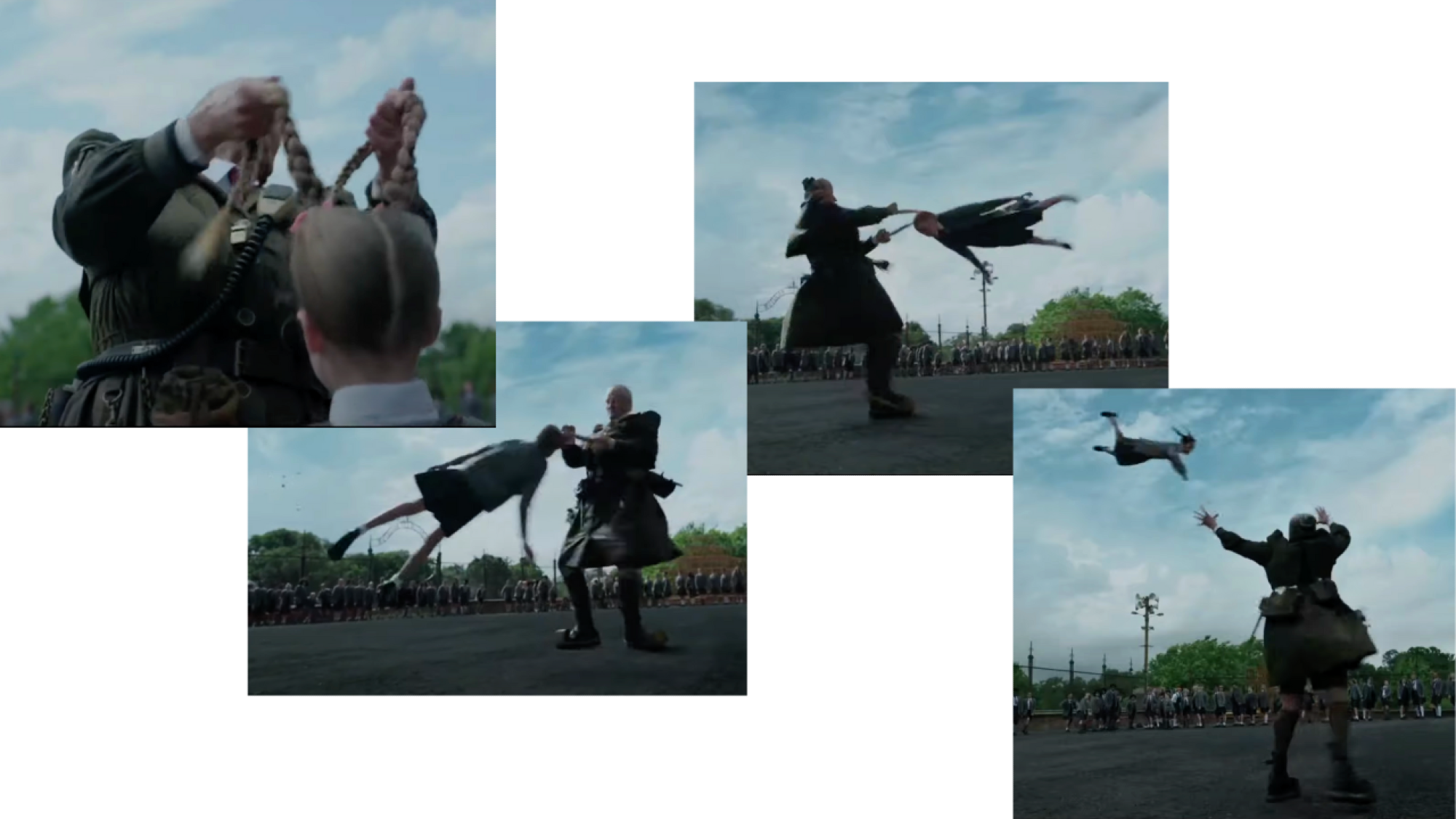

Last week I drew on material from Matilda the Musical to illustrate the importance of respecting a student’s level of interest and capacity when attempting to instruct them. Those familiar with the show appreciated the ominous references to “Phys Ed”!

“Phys Ed” is a euphemism for Miss Trunchbull’s favorite pastime: instilling terror in her students and compelling them to perform harsh drills under threat of even more horrific punishment. The fact that this story is so relatable to viewers testifies to the abuse, or at best neglect, so many of us endured at the hands of our PE teachers.

I am still recovering from the trauma of being compelled to create and perform a solo gymnastics floor routine in front of my entire grade in PE every year in middle school. I could barely manage a somersault. My instructors never even attempted to teach me how to manage a cartwheel or a handstand, so my performance consisted of a series of poorly executed somersaults linked together by some apologetic dance moves, while everyone watched and snickered. If my PE teachers knew anything useful about my anatomy, they kept it to themselves.

That’s another thing that is extremely important to bear in mind: It’s one thing to know about anatomy in the abstract, but quite another to apply that knowledge to the training of someone else’s anatomy, given that each of our bodies is unique. A gifted athlete presents with an anatomical configuration and learning capacity that may differ greatly from, e.g., a student with a congenital disability.

Opera singer, actor, and advocate David Salsbery Fry has hemophilia. David discusses his public school PE experiences in “Internalized Ableism in Disabled Students: Strategies for Learning Support”*, a chapter he contributed to the forthcoming textbook Disability and Accessibility in the Voice Studio. He shares that because “the normal physical education curriculum remained too hazardous” for him,

My school attempted to create an alternate program for me, but the P.E. teacher rebelled and refused to continue to provide me with one-on-one time out of embarrassment and disgust at my lack of coordination. I distinctly remember several missed basketball free throws in a row, resulting in sighs of exasperation and rolled eyes on our last day working together. I was eleven years old. After that, their “accommodation” was to lock me in the gym’s supply closet during P.E. class. The boredom and isolation was stifling.

Their accommodation was to lock him in a supply closet. Matilda fans will appreciate the resemblance to Miss Trunchbull’s torture cabinet, aka “the chokey”.

This is why I said that the answer to the question, “How much does a middle school PE teacher really need to know about anatomy?” may actually be, “Nothing.”

The serious answer is that PE teachers need to know not only a great deal about anatomy, but also a great deal about how to respect and nurture the unique anatomy of every individual student who comes to them for instruction.

A superficial, conceptual acquaintance with anatomy may be sufficient to obtain the documents that qualify one to teach PE. The ability to discuss anatomy without sounding like an idiot may be sufficient to land a job. But only a deep conceptual and experiential knowledge of anatomy enables one to actually teach and accommodate every student and potentially instill them with a love of movement and respect for their own bodies that could last a lifetime.

Imagine how amazing it would be if, as children, we had robust support for learning how to move, coordinate, and strengthen our growing bodies built into our primary and secondary school curricula.

If we had teachers who understood enough about our developing anatomy to be able to accommodate our individual interests, needs, and capacities while we learned how to move, coordinate, and strengthen our growing bodies.

If we had teachers who could teach us not only how to explore and develop our own bodies, but also how to respect our peers and to understand that each of us has unique interests, needs, and capacities.

I see no downside.

Other than the likelihood that Matilda the Musical would never have been written, in the absence of the grotesque but relatable reality that served to inspire its composition!

Next week I will be on vacation, so look for my next post in two weeks’ time. If you have a topic you would like me to explore, please let me know!

*David Salsbery Fry, “Internalized Ableism in Disabled Students: Strategies for Learning Support,” in Disability and Accessibility in the Voice Studio, ed. Katherine Meizel and Anne Slovin (Open Educational Resources, Forthcoming), https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/oer/

If this essay resonated with you, please subscribe to my Ghost. Subscriptions can be either free or paid.

- Your attention is your most valuable currency, so free subscriptions are deeply appreciated!

- Paid subscriptions from those who can comfortably afford it help transition my writing from unpaid to paid labor.

Schedule a complimentary consultation for voice lessons here.

Schedule a voice lesson here.