Range

Singing is a process of musical expression that is facilitated by internal physical movements. As a voice teacher, part of my job is to help singers condition their vocal anatomy, which includes improving range of motion, continuity of movement, and continuity of sensation.

I once served on a panel at a NATS conference alongside Scott McCoy, author of Your Voice: An Inside View. He was asked, “How much does a voice teacher really have to know about anatomy?” He responded, “Enough to avoid saying anything that will make you sound like an idiot!”

We all laughed, and then he proceeded to unpack what he meant, which was that being conversant in vocal anatomy often does not translate to the ability to help singers train their vocal anatomy, which is essentially the point of voice lessons.

How much does a voice teacher really have to know about anatomy? This panel discussion took place two years before my own book on vocal anatomy and biomechanics was published, and I was still in the process of sorting out my answer to that question. At the time, I believed voice teachers needed to know everything I put into my book—after all, that’s why I wrote it!

But while I certainly needed to know everything I put into my book, I am somewhat skeptical that it is essential for voice teachers to have a robust conceptual model of vocal anatomy and biomechanics in their heads while they’re teaching.

This post offers my current view of how much voice teachers (and singers) actually need to know about anatomy, in order to train it effectively.

As promised, I am going to describe some techniques that teachers can offer singers to promote the release of tension and expansion of range of motion for their breathing and vocal anatomy. These techniques are based on some fundamental premises:

- Singing is a process of musical expression that is facilitated by internal physical movements.

- Expanding our vocal options requires both conditioning and coordinating our anatomy.

- The “conditioning” part has to do with improving range of motion, continuity of movement, and continuity of sensation.

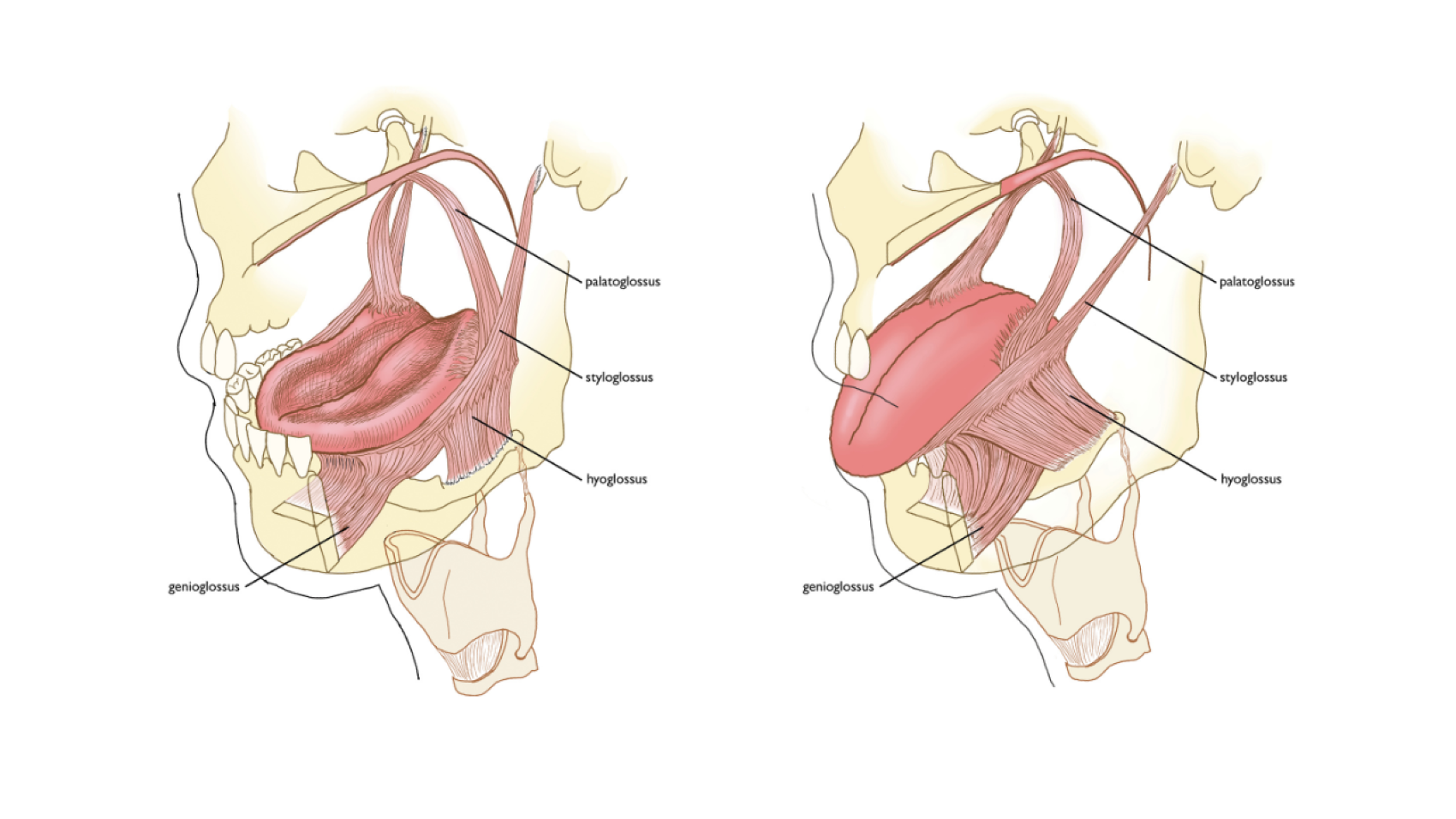

- The “coordination” part includes deconstructing habituated movement patterns and learning to exercise control over individual anatomical components (e.g. learning to move your tongue and jaw independently from one another).

- The means whereby we condition our vocal anatomy has a lot more to do with improving flexibility and interoception than it does with increasing force production (aka strength).

It follows that what we really need to know about anatomy is 1) whether we can move our own anatomy in the direction that we want to, as far as we want to, or not, and 2) if we can’t, there is a reason, and that reason has to do with range of motion, which can be improved.

You don’t need to know where and what your cricothyroid muscles are in order to sense that you can’t sing as high or low as you would like to. You don’t need to know how your diaphragm works in order to detect the possibility of breathing more expansively than you presently can. You don’t even need to understand why the imperative to “Sing from your diaphragm!” makes zero biomechanical sense. All you need is the ability to feel how things are moving, where they are getting stuck, and the concept that the solution involves expanding the range of motion of the stuck structures.

That’s it. That’s all you really need to know about anatomy.

Singing is a process of musical expression that is facilitated by internal physical movements. As a voice teacher, part of my job is to help singers condition their vocal anatomy, which includes improving range of motion, continuity of movement, and continuity of sensation. The modalities I apply include:

- External self-massage using myofascial release tools like massage balls

- Internal massage using the breath

- External vibration using a variety of large and small vibrating objects

External Self-Massage with Myofascial Release Tools

In addition to teaching voice, I became a fitness trainer more than 20 years ago because I realized that if I wanted my students to stand tall and take a deep breath, I needed to provide resources that would actually help them to do those things.

As I pointed out in my previous post, myofascial release is wonderful for addressing chronic tensions that can distort alignment and impede full breathing. The video I appended, How to Improve Your Lung Capacity, includes two stretches that are excellent for alleviating abdominal tension and posterior ribcage and shoulder tightness.

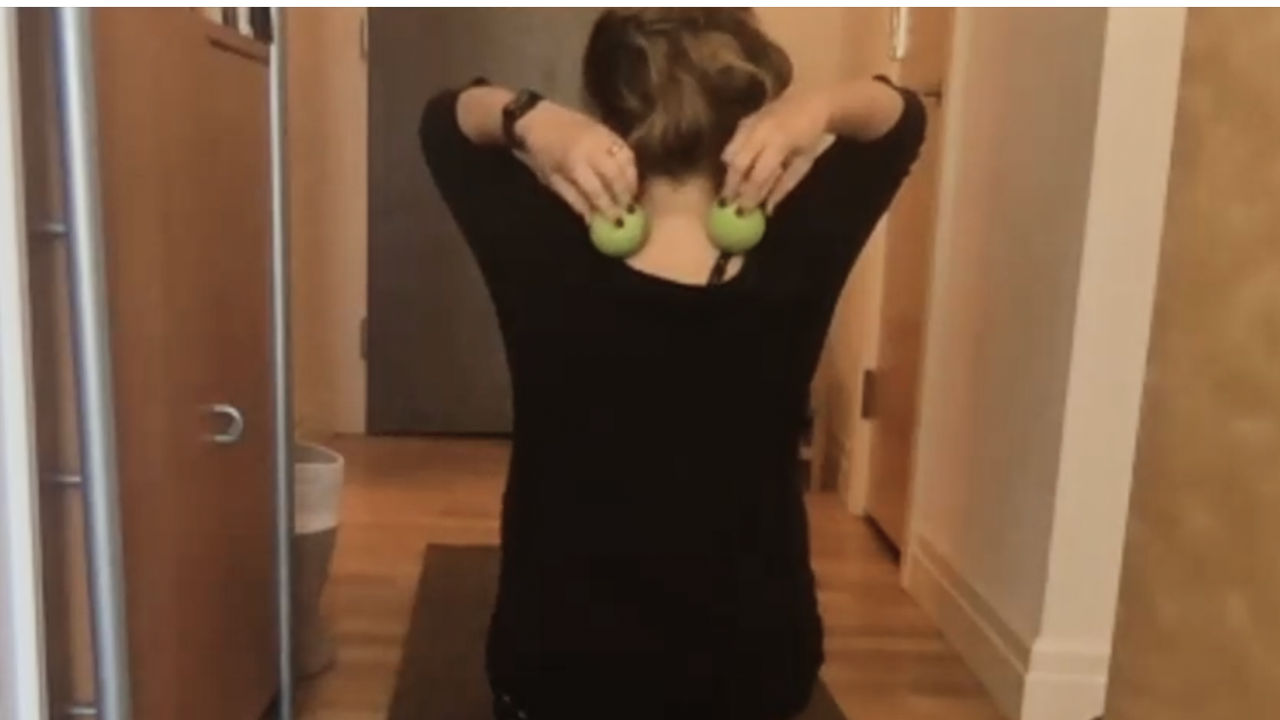

Another good example is the following technique for releasing the upper trapezius.

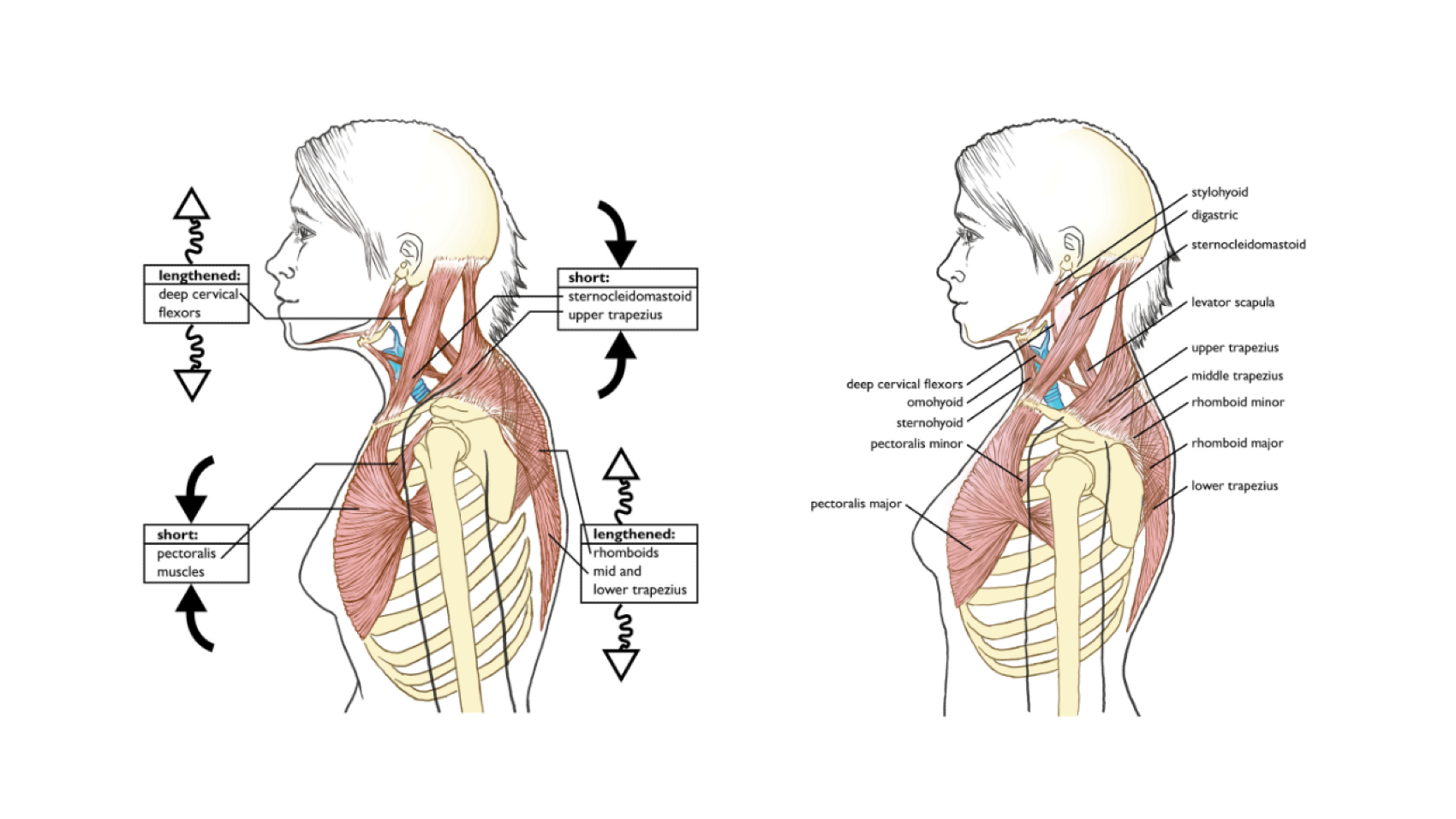

The upper trapezius is an example of a muscle that tends to be tight and overactive, as shown in the illustration of upper crossed syndrome above. When we sustain this common position with the head forward, shoulders internally rotated, and exaggerated neck curvature, the upper traps gradually tighten up and become difficult to relax. This video demonstrates a myofascial release exercise with two small massage balls that is amazing for relaxing and releasing this strong, stubborn muscle.

Internal massage using the breath

While external massage can help increase range of motion for your breathing, the breathing process itself provides you with a perpetual internal massage that supports many physiological processes, including lymphatic circulation, digestion, and, as discussed, nervous system regulation.

This video gets into one of the stretches in How to Improve Your Lung Capacity in greater detail. When you lie on your back with your ribcage propped up as demonstrated, you can feel how your breathing expands and stretches your upper body from the inside. Where your ribs make contact with the ball, you can sense a stretch on the outside throughout the breathing cycle, while also feeling an internal expansion and stretch created by inhaling, and then an internal relaxation and settling while exhaling.

Awake or asleep, breath continually massages your insides. Heightening your awareness of the breath’s role in this internal massage can increase its effectiveness in that role and habituate better, deeper breath coordination for your singing.

External vibration using a variety of large and small vibrating objects

Remember back when we thought vibrators didn’t belong in the voice studio? It’s been a minute since David Ley and Elissa Weinzimmer electrified the vocal world by preaching the benefits of personal massagers!

Without question, the Vibrant Voice Technique exercise that I apply most frequently in my studio is the one for jaw release. When using external vibration to promote myofascial release, be sure to hold the vibrator against the muscle you are massaging in one position while slowly contracting and releasing the muscle. In the video below, for example, I hold the vibrator in a steady position against my masseter and temporalis muscles while slowly opening and closing my jaw.

All singers really need to know about their own anatomy is what they can discern through their own interoception—the ability to feel how things are moving and where they are getting stuck. All they need to condition their own anatomy is some skill at expanding the range of motion of the stuck structures. The modalities I recommend include external self-myofascial release, intentional internal massage with the breath, and external vibration for introducing movement and sensation into tight structures.

Voice teachers can safely and effectively teach these modalities, provided they take the time to explore how their own bodies respond to them and that they understand that how they respond to the exercises will necessarily be different from the way their students respond.

That covers the conditioning part of my pedagogy! Next week I’ll get into the coordination part.