Support

A supportive teaching practice requires strong communication and an atmosphere that feels safe and affirming to the student.

When you’re speaking or vibing with another person, what clues help you to detect whether you understand one another well, or whether there is a disconnect?

Have you ever experienced an interaction where you thought you were both on the same page, and only later discovered that there had been a misunderstanding, maybe even a big one?

Of course you have. We all have. I would go so far as to say that anyone who hasn’t had an experience like this, isn’t doing it right—something that as a teacher, I am generally loathe to say!

No matter how much you may have in common with another person, it is arguably what makes you different from one another that makes your relationship interesting. Among other things, you get to learn from them what it is like to not be you. However, our individual perspectives lend some degree of bias to all our interactions, particularly regarding the precise meaning of words and concepts.

For example, both of you thought that you meant the same thing when you agreed to meet up “soon,” but one of you meant “in an couple of days,” while the other meant “in a month or two.” Saying “I love you” can mean very different things depending on the relationship and the context.

Some misunderstandings are easier to sort out than others!

While there is hopefully less drama in your voice studio than there tends to be on stage, it is still vital to communicate in a way that promotes both conceptual and experiential understanding. That is true for both the teacher and the student, as each has useful information that the other does not:

- The teacher can see and hear what the student is doing, externally.

- The student is aware of their own internal sensations, movements, and thoughts.

The better they are each able to communicate this information to each other, the more successful the lesson will be, not only where learning is concerned but also the quality of their individual and shared experiences.

In my previous post, I proposed that facilitating high quality experiences in the voice studio involves holding space for yourself and your student, in order to help them feel safe, seen, and supported. “Holding space” is a good example of a term that we hear a lot these days, that may mean very different things to different people. For me, holding space means striving towards consistent careful listening and attentive observation throughout the lesson. This is a considerable paradigm shift from the way I was first taught, and the way I also used to teach, with the focus primarily on the content being covered and the results to be achieved. While the learning and performance results (aka the outcomes) are important, they are better achieved when the student feels safe exploring beyond their comfort zone, valued for who they are, and supported in their process (aka the quality of their experience). As a teacher, I will also enjoy a much higher quality experience throughout the lesson when I focus on holding space for them in this way than I will if I am stressing out about whether they will get the point and make a decent sound before the hour is up.

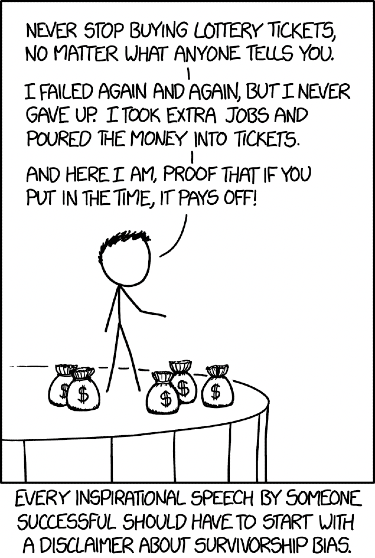

Holding space is more easily defined than done, which is why I experience teaching as a practice in the same way that I do singing. Being able to hold space in this sense requires moment-to-moment mindfulness in any context, but I feel that in the voice studio the practice is made more challenging by the prevalence of survivorship bias in our culture.

“Survivorship bias” means assuming that because something worked for you, it will work for everyone else, too. This is why we mistakenly expect someone who is a great singer to also be a great teacher. We think, well, they figured out how to do it, so they will be able to get their students to do the same things they did, with similar results. They agree. And they sometimes succeed, at least where some of their students are concerned.

But consider what I said earlier, about how the teacher knows only about what they are able to see and hear externally, while the student knows about their own internal sensations, movements, and thoughts. A teacher whose methods stem primarily from survivorship bias (“you want to be like me, so do what I do”) will focus primarily on the extent to which the student’s singing looks and sounds like the teacher’s, and the teacher may not appreciate the usefulness of understanding what the student is thinking and feeling. The student’s primary focus is likely to be on imitating the teacher and assessing the extent to which they are succeeding. Both are likely to evaluate the lesson in terms of outcomes rather than the quality of experience that the hour afforded. A great singer can also be a great teacher, but if they rely on survivorship bias they will be significantly less helpful for those students whose voices and/or temperaments do not closely resemble their own.

Learning to sing often means applying abstract concepts (“support,” “placement,” “passaggio”) to internal movements that can be tricky to sense, describe, and coordinate. That is why in addition to good communication between teacher and student, it is so important to help singers communicate better with themselves by developing skill at interoception—the ability to sense, communicate with, and engage the internal anatomy that performs all of the breathing, phonating, and resonating.

These internal movements can feel subtle and difficult to detect, and it is much easier to focus on them when they don’t have to compete with thoughts and feelings related to outcomes or self-assessment. My next post will talk more about how to improve your interoception, and/or help your students to improve theirs.