Talent

When someone seems to have a naturally beautiful voice, all that means is that they intuited how to move their articulators in a way that provides for more expansive, consistent resonance. It absolutely does not mean that what they intuited cannot be developed—it can.

Do you find it easier to vocalize on vowels than to sing song lyrics?

That your voice is resonant and flowing when you practice exercises, but your resonance and flow are somewhat diminished when you practice your rep?

What if I told you there’s a neat trick that would change all of that?

There unfortunately is no neat trick that would instantly make your singing consistently resonant and flowing. However, I can offer you a rock solid strategy to make your singing progressively and perceptibly more resonant and flowing over time. And I will. First, a brief detour to talk about talent.

These days we hear all the time about how talent is overrated. In The Talent Code, Daniel Coyle argues that there actually isn’t such a thing as innate talent, unless what we mean by “talent” is the embrace of skillful, committed practice. While he has a point, we remain a culture that is utterly obsessed with the discovery and adulation of talent, particularly where singing is concerned. What other explanation could there be for the proliferation of TV talent shows like Star Search, American Idol, The Voice, and America’s Got Talent?

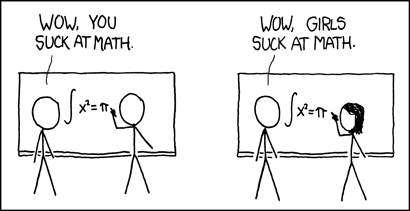

One of the things I find fascinating about these shows is that the B-roll footage always shows the singers who have advanced a few rounds working with vocal coaches. We see them improving, and they talk about how much these coaches helped them. This demonstrates that your skills can be improved, provided you have talent in the first place. The unspoken implication is that in the absence of talent, there’s no point trying to train you. The same thing holds true for other pursuits—it’s the kids who demonstrate an aptitude for sports, math, etc., who get the specialized training.

So no matter how vociferously we proclaim that talent is overrated, we remain a culture in love with discovering talent. If someone does not demonstrate an early special aptitude for something they enjoy doing, they are at risk for internalizing the myth that there is no point in training them.

Thus talent—the way that a given skill seems more intuitive and accessible for some people than it is for others—is not overrated. It is true that talent alone will only get you so far, and that’s the reason for all the B-roll coaching footage, not to mention scholarship funding for Juilliard students. But many, many people who long to sing are surely watching these TV talent shows and sighing, wishing that their voices were more beautiful, flexible, and expressive, and believing that they never can be.

I am confident that many, even most of these would-be singers, do have the aptitude to learn to sing the way they long to. Their biggest obstacle is the internalized belief that they lack talent.

In The Talent Code, Daniel Coyle attempts to redefine talent as the ability to practice strategically and consistently, but his reframing is far less useful than I wish it were. I say this because the most important prerequisite for practicing intelligently and consistently is the belief that it will get you the results that you are after. It is very difficult for that belief to take root when it is in competition with the powerful, internalized, unconscious assumption that only the intuitively gifted will succeed.

Now I am going to explain how you can make your singing more consistently resonant and flowing. However, I can’t persuade you that applying these ideas strategically and consistently will get you the results that you are after. That is something you will have to discover for yourself, and you will likely encounter and need to vanquish internalized beliefs about aptitude along the way.

When we refer to beauty of vocal tone, what we are talking about is resonance (the link is a one-minute video I made that offers a solid explanation). We resonate our voices by shaping the highly malleable space inside our mouths and throats. Resonance is a skill that can be developed and expanded.

Do some people have naturally beautiful voices? I honestly don’t know. What I do know is that I initially brought a great deal of throat, tongue, and jaw tension to my singing, and that when I was able to alleviate that tension and train my articulation and resonance anatomy, my voice became progressively more beautiful. Helping my students to do likewise has yielded similar results for them.

Alleviating tension is a part of conditioning our vocal anatomy. In this post, I will apply the ideas I shared last week about how to coordinate our vocal anatomy for articulation—how we move our mouths to produce the vowels and consonants that comprise song lyrics.

Take a moment to recite the lyrics of a song you love (or just read this sentence out loud). Observe all of the movements your mouth is making, either by watching yourself in a mirror or feeling the movements with your hands. What you are observing is the coordination you developed for speaking, by watching and listening to the people around you.

Each distinct sound you make is the result of a combination of jaw, tongue, lip, and soft palate movements that you have been habituating since you first learned to speak. While those movement combinations are perfectly adequate for you to make yourself understood in conversation, they are unlikely to yield consistent, beautiful resonance for your singing.

When someone seems to have a naturally beautiful voice, all that means is that they intuited how to move their articulators in a way that provides for more expansive, consistent resonance. It absolutely does not mean that what they intuited cannot be developed. It can! It just requires deconstructing your speech habits and coordinating your articulators with greater intention. In other words, learning to move your jaw, tongue, lips, and soft palate independently from one another, and then learning to engage each only when desirable.

This requires patience and observation. It also requires focusing your awareness on just the movements involved in articulation, while disregarding anything that does not have direct relevance for articulation. Paradoxically, because the practice you are engaging in is an intermediary step in the development of full resonance, you may struggle to imagine that the way your voice sounds to you when you are training your articulators is among the things necessary to disregard. That is a dealbreaker for many singers—they’re so focused on the outcome of improved resonance that it can be very difficult to practice the movements that are essential to elicit that outcome.

One of the first things I learned as a fitness trainer is that making changes to habituated movement patterns requires intense focus, strong interoception, and mindful repetition of new coordination. Something else I learned is that most of the people who came to me for training just wanted me to tell them what to do, make them do lots of reps and sets, and keep an eye on their form. Teaching them to keep their own eyes on their form was a really tough sell.

I find that voice lessons often follow a similar paradigm. The expectation is that the teacher will tell the student what exercises to do, how many repetitions to perform, and provide feedback on their sound and coordination. But for meaningful progress to occur, the student must learn to observe, evaluate, and make changes to their own internal movements, given that making changes to habituated movement patterns requires intense focus, strong interoception, and mindful repetition of new coordination, and that most of this work is going to occur outside of a weekly (monthly? randomly scheduled?) voice lesson.

Try this exercise for tongue/jaw coordination: Say ah-nah-nah-nah-nah while observing yourself in a mirror or feeling your mouth movements with your hands.

Now say it again, while allowing your jaw to remain in a slightly open, relaxed position, and just moving your tongue to articulate the n sound.

Unless this is something you have already worked on, my guess is that very few of you will be able to do it. Because most of us learn to make the n sound by moving the jaw. We learn to articulate all of our consonants by moving the jaw, even though a majority of consonant sounds are possible to articulate without moving the jaw.

So if you find it easier to vocalize on vowels than to sing song lyrics, that is one of the big reasons. You are closing your jaw every time you articulate a consonant, and the movement unnecessarily diminishes your resonance space. When a consonant does require jaw movement, it’s important to learn to execute that movement swiftly. There are other significant components of articulation coordination that contribute to consistent resonance and flow, including, for example, learning to engage the lips more than we generally do in habituated speech. But these components are finite in number, and all can be learned and integrated into your articulation and resonance strategies.

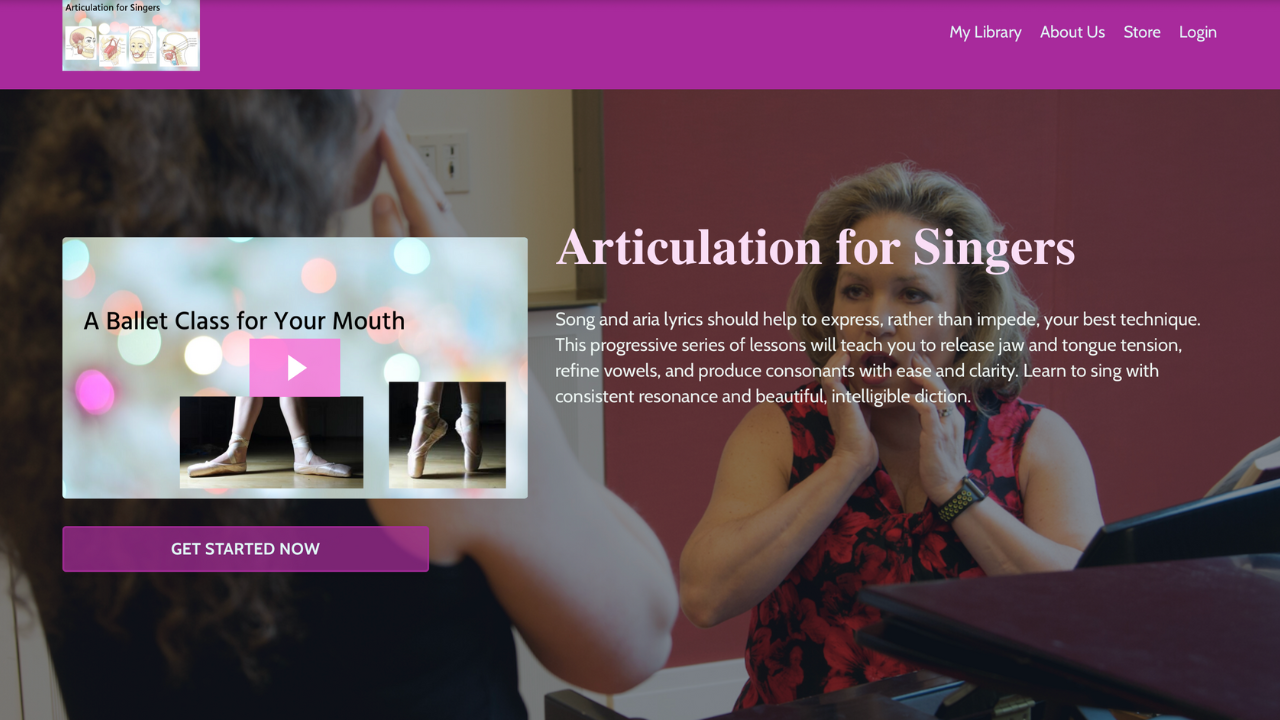

I built my Articulation for Singers self-study course because I realized that advising my students to “move your tongue and not your jaw” over and over again wasn’t cutting it. I included exercises for pretty much any sound you would need to articulate in several languages. To thank you for following my blog and to support your practice, I’m offering it to my readers for free for a limited time.

All I ask in return is that you give it a whirl! Your awareness is your most valuable currency. If you would also like to show your appreciation via more tangible currency, please subscribe at the Ah, Capitalism or Production Value levels.

The neat trick that will enable most anyone to learn singing, regardless of apparent aptitude, is breaking down the complex movement combinations involved in singing into the simplest possible components, homing in on each with your awareness while disregarding everything else, and then intentionally integrating the movements with mindful repetition.

I can teach my students to do this while they are with me, but the work we do together only leads to retention and solid coordination when they engage in mindful repetition of the skills we covered. No matter how motivated they are, that can also be a tough sell, thanks to the educational paradigm that greets us right from elementary school. That will be the topic of next week’s post.