Value

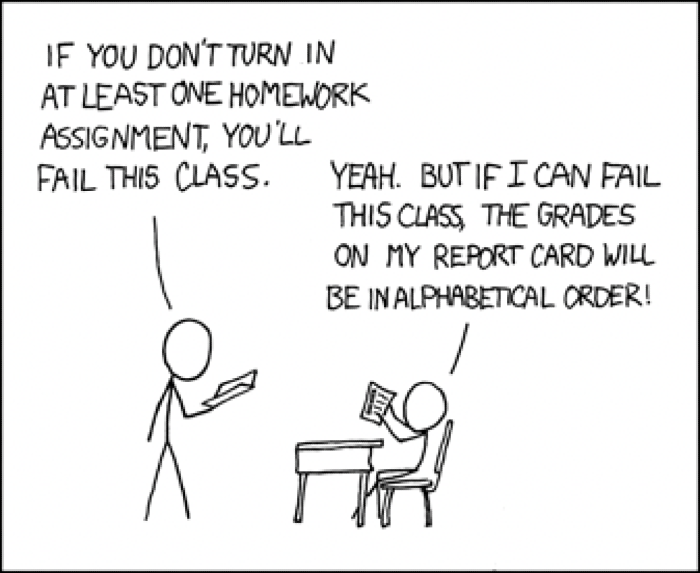

Grades reduce learning to a common denominator and rank students against one another, creating a situation where external validation by a teacher and comparative success over their peers become more important than actual learning.

Did the grades you received for your schoolwork support your learning?

Did the grades you received for your schoolwork support your enjoyment of learning?

Did the external validation of good grades mean more to you than the things you were studying?

Did the humiliation of poor grades make you feel diminished and hopeless about improving?

I remember learning to read. I don’t mean the learning process—I mean the actual moment I understood what reading was. I remember it like it was yesterday.

I was six years old, in the first grade. One moment I was staring at meaningless symbols on a page, and the next moment those symbols coalesced into words, then paragraphs, then an entire story, right before my eyes.

It was love at first sight. I was instantly enraptured with words, stories, reading, and writing. And I still am! It is magical to be able to weave thoughts into words and share them where others can find and engage with them.

After that moment, I always had my nose in a book, or so the complaints usually went. In class, I did my best to pretend I was paying attention while surreptitiously glancing down at the open pages hidden in my cubby desk. Having now been a teacher myself for several decades, I am quite sure that my elders were aware that I wasn’t giving them my full attention, but as I was still paying enough attention to earn good grades, they mostly let it slide.

I kept up this strategy, more or less, until I graduated high school. I paid attention when the subject was something I cared about—literature, music, and math. When the subject was something I didn’t care about, I paid enough attention to earn good grades, while covertly studying something I did care about.

In retrospect, I can appreciate how my aptitude for book learning conferred a type of privilege on me. I was able to earn good grades without breaking a sweat, and I was able to ace the SAT without much study. I can also appreciate how my enthusiasm for learning conferred another type of privilege on me, which was that I didn’t really care about the grades I earned. If it was a subject I cared about, the learning was satisfying in and of itself; if it was a subject I didn’t care about, I could check out, usually without consequence.

Thus it was that I was able to graduate high school with my love of learning intact.

I had such high hopes for my college experience. My fantasy was that now I would be amongst peers who shared my enthusiasm for learning. I imagined burning the midnight oil with them while pondering big, eternal questions. I envisioned a musical community awaiting me that was bursting at the seams with creativity and passion.

What actually greeted me was Western Lit 101 in an enormous lecture hall with an enormous reading list, taught by one grad student while others critiqued and graded our papers. What actually greeted me was a music program so competitive that I was unlikely to get more than a couple of lessons with the clarinet teacher I had hoped to work with, and forget about playing in the orchestra.

So right from the start, it was very challenging to keep my love of learning alive in this environment. What inevitably made it impossible were the grades. This wasn’t high school—I couldn’t squeak by with the bare minimum and expect to earn good grades. My life became this debilitating grind of reading books too fast to fully enjoy or comprehend them, then writing papers that would meet the expectations and standards of the grad assistants.

The point was no longer the learning. The point was busting my ass to study things I derived no pleasure from in order to earn good grades.

I lasted less than a year.

I have since come to appreciate how the trauma and indignity of studying for the grade is a lot more pervasive and problematic than I was able to discern from my first attempt at undergraduate education. In retrospect, it seems nothing short of miraculous that I was spared something that surely befell most of my fellow students, which is that until college, my love of learning was never polluted by the threat of Bad Grades.

Grades are evil. Grades are the enemy of learning. Grades are really bad for us.

If a child has aptitude for something and enjoys it, they have motivation to engage with and excel at it. They may need encouragement and instruction, but they do not need an evaluation of their work that ranks them against their peers.

If a child initially shows little aptitude for but great enjoyment of something, they have motivation to engage with it. With encouragement and instruction, they may yet excel at it. An evaluation of their work that ranks them against their peers would likely destroy their enjoyment and deflate their motivation. Nobody needs that.

If there is a subject a child does not enjoy… why make them study it in the first place? If it is something like reading or math, i.e. a skill that they will need to function in society, the first hurdle to clear is helping them to understand why it would be of value to them. If you compel them to engage with and excel at it while ranking them against their more motivated peers, you set them up for misery: “Here is this thing we are forcing you to do that you dislike, and we are going to make you feel bad about disliking it and sucking at it by comparing you with people who like and excel at it”. That does not make for a solid pedagogy.

Grades reduce learning to a common denominator so that we can rank students in comparison with one another, without regard for motivation or aptitude. They create a situation where external validation by a teacher and comparative success over their peers become vastly more important than the learning itself.

Last week, I wrote, “The work [my students and I] do together only leads to retention and solid coordination when they engage in mindful repetition of the skills we covered. No matter how motivated they are, that can be a tough sell, thanks to the educational paradigm that greets us right from elementary school”.

Meaningful development of skill, particularly in the arts, is fueled by individual passion and internal motivation. Learning to sing well requires engaging in regular practice. The focus and structure of the practice will be different for different singers. A practice motivated by curiosity and creativity will yield both enjoyment and progress. The issue is that we have been deeply conditioned to seek external validation of our pursuits, while being compared with/ranked against others. That conditioning and those comparisons are likely to haunt our practice.

Do you feel guilty when you think you don’t practice enough?

Is your enjoyment of music-making entangled with thoughts about how you compare with others?

Do you love music as much now as when you first fell in love with it?

These days, particularly in light of my recent cancer adventure, I value music for what it does for me as an individual, and what it can potentially do for ensembles and audiences. It can get us in tune with our own feelings and expressive impulses. It can sync us up in really cool and creative ways. It can inspire deep feelings in the listener. I value making music for the way it affirms our individual and collective voices.

This is essentially the opposite of the way TV talent shows “value” music. These are competitions designed to validate a “winner” who beats out everyone else. They rank singers against one another and often play the “losers” for laughs. And the reason they garner so much attention and are so successful is that they are supported by audiences who were conditioned to believe that the ranking, not the music, is the point.

My college story actually had a delightful ending. I eventually enrolled at Bennington, a small liberal arts college where I found myself amongst peers who shared my enthusiasm for learning. Together we burned the midnight oil and pondered big, eternal questions, and shared a musical community that was bursting at the seams with creativity and passion.

They don’t give grades at Bennington.

I am so grateful that my love of learning has proved so resilient over the years. Next week I want to talk about the importance of inspiring a love of learning in others and share some ideas for how to go about it.